At the far end of the courtyard what once was a fountain, fed water into a pool in the middle.

The fountain flowed from an open arched room covered with mosaics, the work of David Ohannessian who came to Jerusalem in 1919.

The triangular wedges are made of dark blue glass set in a white clay and surrounded by mosaics in shades of blue and turquoise. David Ohannessian used only these colors, sett off by an occasional reddish brown. His designs are geometrical and exact, much in the tradition he brought with him from Kutahya in Western Turkey.

Today virtually all visitors to Jerusalem (and the locals as well) regard Armenian ceramic ware as a local Jerusalem trademark. In fact it originated neither in Jerusalem nor from the Armenians. The tradition was imported to Jerusalem by David Ohannessian from his hometown of Kutahya. There he had learnt his trade in the Turkish/Moslem tradition, which itself had borrowed from 12th and 13th century Tabriz (in Iran) in pre-Ottoman Islamic times. Tabriz ceramics derive from an ancient tradition going back to early Mesopotamia.

The circles and triangles in this 13th century ceramic from Tabriz, or others like them, seem to reappear in Ohannessian’s 20th century work. [For specifically Turkish ceramics see Dr. Sitare Turan Bakir].

David Ohannessian, as a young Armenian had already developed a reputation as a master craftsman, whose work – despite his Christianity – was in great demand for the restoration of ceramics in Turkish mosques. It may well have been his expertise that saved his life when Turkey embarked on its purge of Armenians (whom it regarded as a possible Russian front in the First World War – and the Armenians had rebelled in the 1890s) on April 24, 1915. Together with hundreds, maybe thouands, of other Armenians, Ohannessian took his family first east and fled south, landing up in Haleb [Aleppo]. There, says his son (at the time a very young boy), the Armenians were rounded up and led out into the desert, when suddenly an Arab horseman in flowing robes came riding out of nowhere calling for David Ohannessian, who stepped forward, sure this was his last moment. But the story ended well – for him; the Pasha of Katahya, reluctant to lose his master restorer, had been searching for him everywhere. The family was taken back to Haleb, none of the others were ever seen again.

Circumstances of the war kept the Ohannessian family in Haleb and in 1919 David was invited by Sir Ronald Storrs, after World War I the British Governor of Jerusalem, to restore the ceramics on the Dome of the Rock. The medium in this passage was Sir Mark Sykes, who had known and befriended Ohannessian since 1911.

In 1911 Sledmere, since 1748 the Sykes family estate in the rolling hills of the Yorkshire Wolds, was almost totally destroyed by fire. The buildings were restored by architect Walter Brierley, with the exception of an exotically tiled Turkish room, reflecting the Oriental tastes of the young Mark Sykes, who found in Turkey the man to do the job, David Ohannessian. Renewing his acquaintance with him in 1919, he suggested to Storrs that Ohannessian was the man to restore the Dome of the Rock. Storrs, who had a vague memory of the artist who had tiled Sykes’s ‘bathroom’, arranged for Ohannessian to come to Jerusalem.

The majestic dome over the Rock on Haram as Sharif (The Noble Sanctuary, better known as the Temple Mount) is supported by a vast octagonal building, decorated with ceramic tiles by craftsmen from Tabriz, brought to Jerusalem in the 16th century by Suleiman the Magnificent. Ohannessian, realizing he would need help, sought a potter and a painter. Unable to find anyone suitable locally, he went back to Turkey where he found Nishan Balian and Megadich Karakshian. The project of restoring the Mosque went so slowly that the three looked for a way to make a living; they began to make tiles to sell in their new workshop on the Temple Mount. The Moslem religious foundation, the WAQF, didn’t take kindly to the Noble Sanctuary being turned into a place of trade and the trio broke up.

The majestic dome over the Rock on Haram as Sharif (The Noble Sanctuary, better known as the Temple Mount) is supported by a vast octagonal building, decorated with ceramic tiles by craftsmen from Tabriz, brought to Jerusalem in the 16th century by Suleiman the Magnificent. Ohannessian, realizing he would need help, sought a potter and a painter. Unable to find anyone suitable locally, he went back to Turkey where he found Nishan Balian and Megadich Karakshian. The project of restoring the Mosque went so slowly that the three looked for a way to make a living; they began to make tiles to sell in their new workshop on the Temple Mount. The Moslem religious foundation, the WAQF, didn’t take kindly to the Noble Sanctuary being turned into a place of trade and the trio broke up.

In 1922 Karakshian and Balian opened ‘Palestine Pottery’ on Nablus Street (where the ‘Palestinian Pottery’ store/workshop/museum sits today.

The oven of their workshop is today the museum, displaying some old classic pieces.  Balian was the potter, Karakshian the painter. New colors were added, in particular, yellow. Exact geometry was abandoned in favor of freestyle painting. The inscription (on the magnificent 8th century mosaic at Hisham’s Jericho Palace?) which mentions the dead whose place of burial God alone knows, resonated strongly in these survivors of the Armenian massacre and the themes there begin to appear over and over in different colors and variations in their work. The partnership lasted in harmony until 1964 (from 1948 in Jordanian Jerusalem). At this time the members of the next generation – Nishan Balian and Megadich Karakshian having passed on to a better workshop – agreed to go their own separate ways (they remain friends to this day). The Balian family stayed at the workshop, ’Palestine Pottery’ giving way to ‘Palestinian Pottery’, while the Karakshian family opened ‘Jerusalem Pottery’ near the 6th Station of the Cross on the Via Dolorosa.

Balian was the potter, Karakshian the painter. New colors were added, in particular, yellow. Exact geometry was abandoned in favor of freestyle painting. The inscription (on the magnificent 8th century mosaic at Hisham’s Jericho Palace?) which mentions the dead whose place of burial God alone knows, resonated strongly in these survivors of the Armenian massacre and the themes there begin to appear over and over in different colors and variations in their work. The partnership lasted in harmony until 1964 (from 1948 in Jordanian Jerusalem). At this time the members of the next generation – Nishan Balian and Megadich Karakshian having passed on to a better workshop – agreed to go their own separate ways (they remain friends to this day). The Balian family stayed at the workshop, ’Palestine Pottery’ giving way to ‘Palestinian Pottery’, while the Karakshian family opened ‘Jerusalem Pottery’ near the 6th Station of the Cross on the Via Dolorosa.

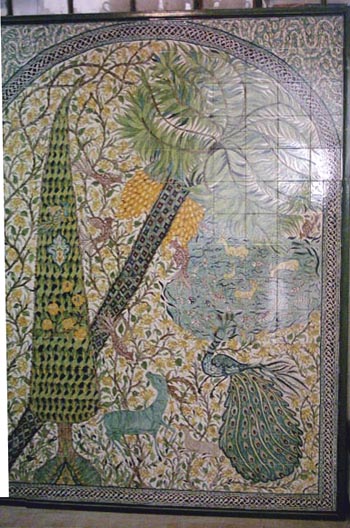

Palestinian Pottery was first run by Nishan’s son Setrak, whose wife Marie studied art in Paris, Marie’s designs began to appear more and more, while she herself remained in the background. Since the 70’s she is in the forefround. Today, on entering ‘Palestinian Pottery’ the visitor is greeted by Marie Balian’s large fir tree/date palm ceramic mosaic.

Inside is the museum, a store and a workshop.

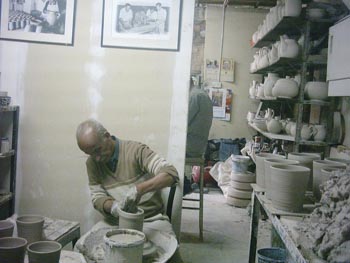

A potter at work today

And the painters

From here we head for Zion gate at the southern wall of the Old City. Sandwiched between the Dormition Abbey (adjoining the traditonal Room of the Last Supper) and Zion Gate are the grounds of the Armenian monastery and cemetery. The path from the entrance leads to the courtyard of the monastery, covered by graves. The only way to proceed is to walk over the dead; Around the courtyard further graves are surounded by the mosaics of the three first artists.

With your back to the entrance facing south Ohnessian’s work is on the left

An insert from 1928 proudly announces his founding of the Armenian school of ceramics in Jerusalem in 1919

On the southern side of this 14th century cloister a group of oval patriarchal sarcophagi are backed by a Karakshian ceramic, his artistry shining through the sad state of repair

Heading back to the entrance we turn left (westward) and enter the cemetery in which rank and file Armenians were, and still are, buried.

Most of the graves are simple – like this smoker’s grave (someone thoughtfully placed an ashtray within easy reach)

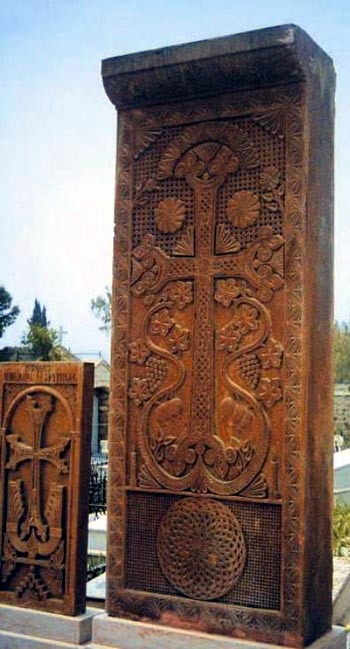

While others have fancy headstones dominated by a stone cross, a ‘karkahya’.

to be continued...